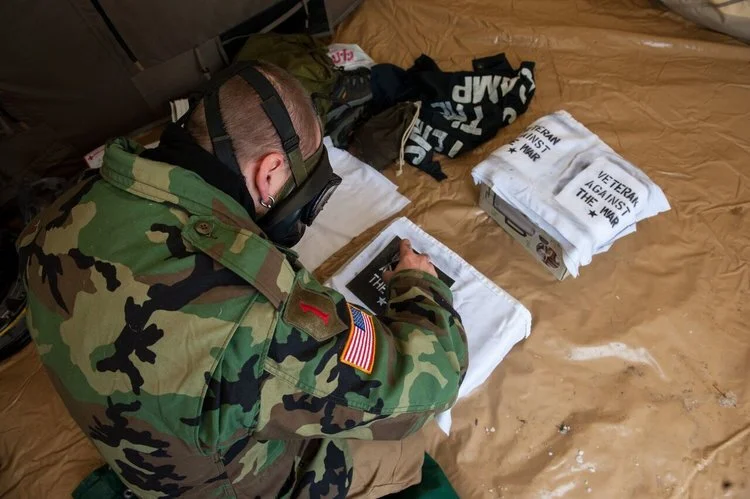

Eli Wright, making stencil patches at Standing Rock (Photo credit: Cole Howard)

By Kevin Basl, originally published on Praxis in Color

In 2014, the Lakota/Dakota Sioux at Standing Rock Reservation began resisting an oil pipeline, scheduled to cross under their water source, the Missouri River. Fearing not only polluted water but also the desecration of sacred sites, water protectors (as they called themselves) established camps near pipeline construction areas, for prayer and resistance. In late 2016, several thousand U.S. military veterans came in support.

Kevin: How long you were you at Standing Rock and what was your role on the ground? What compelled you to go?

Eli: I was there for two weeks, from just before Thanksgiving until December 8. I went with a contingent of Iraq Veterans Against the War [IVAW]. We mobilized to volunteer and to bring donations of supplies and equipment.

I went there also to serve as a medic, which is what I did in the military. When I saw the videos of dogs attacking water protectors—they were calling for medics partially in response to that—I decided to go. As a veteran, I wanted to serve, as I had when I enlisted in the military.

Kevin: Before we talk about art, do you want to say something about cross-cultural sensitivity?

Eli: Absolutely. At Standing Rock, there’s a lot of talk and work around decolonization. Indigenous peoples are making a conscious effort to dismantle so many social structures imposed on them, to rebuild communities with traditional values, to reclaim their cultural identity in sovereignty. As a white, male veteran, I had to acknowledge this and understand my own historical role in that structure, to step back and reflect on these new ways of seeing history. The experience really put a lot of things into perspective for me.

Eli Wright, making stencil patches at Standing Rock (Photo credit: Cole Howard)

Kevin: Do you see parallels between the decolonization of indigenous peoples and the demilitarization of veterans?

Eli: I think there are a lot of parallels. There’s a strong effort within many indigenous communities to reclaim identity and sovereignty, reverse the colonization of their cultures, all the way down to language and individual expression. It made me think about what we do in Combat Paper workshops—how we deconstruct military identity and war experiences and undo some of the trauma that often comes with those, how we reclaim our strength and sovereignty as individuals and reclaim our culture after exiting the military.

Standing Rock was inspiring. I asked myself how we as veterans, artists and activists can learn from other communities and cultures who’ve been long engaged in reclaiming and deconstructing their experiences. How can we keep the good and leave the bad— heal from traumas? I think veterans and artists can work in solidarity with indigenous peoples at the intersection of demilitarization and decolonization. The two are co-occurring—they require each other to function.

Kevin: Beyond veterans offering support on the ground, as many did at Standing Rock, do you see a special place for us in social justice movements or resistance efforts?

Eli: As veterans, we’re given a platform or soapbox, in many cultural arenas, to speak our minds. We’re often asked our opinions around big issues like war and foreign policy—big moral and philosophical issues. If our culture wants to give us this platform for speaking about our experiences, then we should use that privilege to help others. We can share that platform, give oppressed peoples an opportunity to be heard. I think we have a responsibility to do that. And I would go so far to say that anything less than that is complicity in the oppression of these communities. If we choose to remain silent while being aware of the privileges we have as veterans, then we’re contributing to the culture of oppression.

Kevin: Did you see any other interesting things at the intersection of the two cultures? You mentioned the tents at Standing Rock…

Eli: Yeah, one of the really powerful images of the Oceti Sakowin camp was this juxtaposition of teepees and military tents. There was a wide range of military tents of various eras, in both desert and woodland colors. One of the tents we had at the IVAW camp was a WWII or Korean War-era arctic tent. So we were taking this old refuse of military material and repurposing and reclaiming it, using it in this way that was actively and intentionally focused on demilitarizing and decolonizing the space, the community and the struggle. There were so many veterans there of various eras, with a lot of military skills and training being repurposed and put to use. The work wasn’t focused on war-making, but on peace-making. Instead of being there to destroy, we were there to build. We used the very tools of the military—down to foldable shovels and water cans. Military surplus. There’s so damn much of it!

Kevin: What about art? What role has it played at Standing Rock?

Eli: David Solnit helped set up a big art space in a military tent. Some of the artists from Justseeds, and other folks we’ve collaborated with, were there. It was amazing seeing how in sub-zero temperatures—no plumbing, very little electricity—how you can have a functioning art space with screenprinting capabilities. Folks were making art with very limited supplies and equipment. They were reusing water to wash out silkscreens with sponges in bus tubs. We were cutting stencils and spraypainting patches and doing all sorts of cool stuff. We made a flag for the IVAW camp.

It was a reaffirmation of the role the artist plays in social justice movements. Art is a critical aspect of how we build the messaging, identity, and images that portray and archive a movement.

Michael Blake, cutting stencil patches (photo credit: Cole Howard)

Kevin: Any examples of art being used as a nonviolent direct action tactic?

Eli: There was a really brilliant action using “mirror-shields,” planned by Indigenous People’s Power Project. They were largely responsible for conducting the direct action training, teaching nonviolent de-escalation techniques, how to engage with police without getting injured—things like that. Mirror-shields act both as protection and as a way of forcing police to look at themselves, how they’re viewed by the people.

Mirror-shields can also be used to make a sort of living art installation, especially when viewed from above. Some water protectors have personal-sized hobby drones with cameras on them, so they get good aerial shots. They’ve documented the camp experience, and some videos have actually served as evidence to prove excessive police violence on water protectors. But protectors can also face their mirror-shields to the sky, on cue, moving them to create the look of rippling water. You can see it on drone footage.

Water protectors with mirror shields (Photo credit: Cole Howard)

Kevin: I saw an online video where the artist [Cannupa Hanska Lugar] asked people to buy Masonite board and reflective tape—to make shields and send them to Standing Rock. When I was there I saw piles of them—

Eli: Yeah, there were tons of them.

Kevin: It says a lot about social media’s role in the resistance there. The artist released a video online and so many people responded.

Eli: Many people couldn’t go to Standing Rock but offered support in other ways. Artists were creating graphics for making posters and patches and putting them on the Internet. Anyone could download and print them for free. We share media so easily now. It’s a good example of how digital technologies help reach a broader audience, compared to previous social movements.

Kevin: Final thoughts?

Eli: I think veteran-artists can offer an effective and powerful way to help tie together indigenous struggles—and specifically indigenous veterans’ issues—and provide a platform for getting their stories and struggles out to a wider audience. That’s one direction I would like to see our work go in—connecting with Native Veteran communities, amplifying their voices.

But, first and foremost, I went to Standing Rock in service. I was there in support. I was there as a guest, and I think that’s an important thing to remember with social justice struggles. We have to know where our struggle ends and another begins. It’s where those struggles converge that we have to work together. The movement at Standing Rock is historic not because of the pipeline, but because of the solidarity that coalesced around it. It sparked a broader awareness of the Indigenous Rights Movement and its relationship to the Civil Rights Movement, and veterans are suddenly answering the call to serve again in support of this. This is what decolonization looks like.

References:

Mirror Shields: https://vimeo.com/191394747

David Solnit: https://vimeo.com/161333820

Justseeds: www.justseeds.org

Eli Wright: Bio